As GMs and players, we can use status to inform the creation of NPCs and PCs.

Fear the Kool-Aid Drinkers

Perhaps most people have one childhood incident seared in their mind – the moment when something happens out there in the big wide world, and for the first time it registers in your young mind that horrible human behavior isn’t just something that can be found in Grimm’s Fairy Tales or history books. It’s in the here and now.

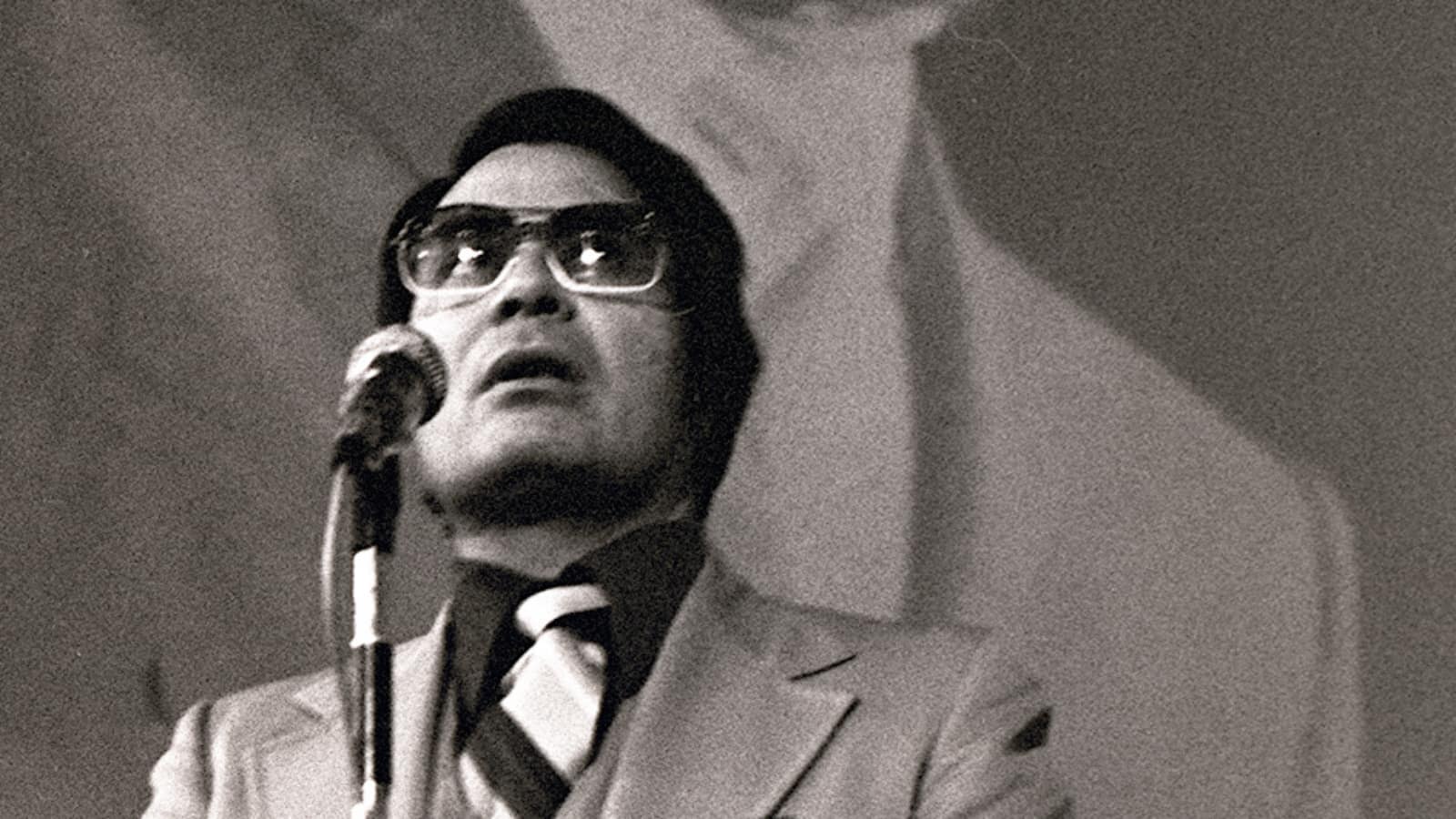

The precursor to that moment for me came on November 18, 1978 – a month before my eleventh birthday. The TV news that night reported that something terrible had happened in a place called Guyana, where followers of a man named Jim Jones had killed Congressman Leo Ryan and several members of his delegation who had been looking into Jones’s “People’s Temple Agricultural Project”, more commonly known as Jonestown. As more details came out over the next few days, I watched it all on TV, compelled and horrified in equal measure.

After the assassination of Ryan, Jones had told his followers that the US government would come after them, and the only viable course of action was mass suicide. That suicide was put into effect through cyanide-poisoned Flavor-Aid. All the children in Jonestown were made to drink it. Parents willingly gave their children poison, at Jones’s instruction. This, by the way, is where phrase, “drinking the Kool-Aid” originated in reference to unquestioning allegiance to an idea, no matter how stupid.

It was that bit right there, the parents giving their own children poison, as part of some sort of insane mass delusion, that freaked me out. Seeing a TV reporter talking about it put an indescribably intense fear into me. I packed that fear into a corner of my mind and resolved never to revisit the topic.

Thankfully years later I mustered the courage to read Raven: The Untold Story of the Rev. Jim Jones and His People, by Tim Reiterman and John Jacobs. Doing so helped me understand a great deal about how a movement that was in many ways very positive in the beginning eventually led 900+ people to come under Jones’s control and wind up dead in the jungle. But it wasn’t really recently that the whole picture came together for me in a way that made some kind of sense.

The Status Game

It was a book called The Status Game: On Human Life and How to Play It, by Will Storr, that filled in the missing pieces. Before I read The Status Game, I assumed that for most people status was about making people jealous because you had a fancy job title, a big house, and money to burn on expensive toys. Whenever I drove around Silicon Valley, I looked at all the Porsches and Maseratis on the road and smugly looked down at all the status-obsessed people driving them, people who were fixated with status. Unlike me.

A few pages into The Status Game, I realized that I too was just as obsessed with status, even if I didn’t admit it to myself. I had simply defined status too narrowly, and hadn’t really understood its role in human society, and how much it motivates all our actions. We are all playing status games, whether we realize it or not, because they’re vitally important to our well-being. Storr repeatedly emphasizes that necessity:

Status isn’t about being liked or accepted: these are separate needs, associated with connection. When people defer to us, offer respect, admiration or praise, or allow us to influence them in some way, that’s status. It feels good. Feeling good about it is part of human nature. It’s in our basic coding, our evolution, our DNA.

Like it or not, we play these games constantly, and usually each game is composed of a mix of these three types:

In dominance games, status is coerced by force or fear. In virtue games, status is awarded to players who are conspicuously dutiful, obedient, and moralistic. In success games, status is awarded for the achievement of closely specified outcomes, beyond simply winning, that require skill, talent, or knowledge.

Take members of a cult, for example. How on earth would a group of people become so deranged that they’d poison their own children? Storr examines a cult in The Status Game, which had initially been known as Human Individual Metamorphosis. The story of the the group differs from the People’s Temple, but the broad strokes are quite similar, in that people who joined the group wound up doing things as members of a group that they never would have imagined until the imperatives of status made those actions inevitable. In 1997, the remaining 39 members of the cult, by then known as Heaven’s Gate, committed group suicide.

Most of us seek status in multiple realms (family, work, friend groups, and so on), and thereby are always playing status games across these domains. But cult members are only playing a single status game – that of their cult. Adherence to the cult’s rules and sublimation of individual motivation and critical thinking provides a sense of worth and belonging that can overwhelm everything else:

Cults are the tightest games of all. They maintain their power by being the sole significant source of connection and status for their players. Earning a place in the cult means actively following its belief system and adhering utterly to its game in thought and behaviour, allowing it to colonize your neural territory entirely. A true cult member has one active identity. Players attracted to them are often those who’ve failed at the games of conventional life. Alienated, injured, and in need, their brains seek a game that seems to offer certainty, in which connection and status can be won by following an absolutely precise set of rules.

My Games Ain’t Your Games

When I was growing up, success games in my family thankfully took a different form. Travel and the worldliness it bestowed was a big part of my family’s success games. When I began traveling on my own as a teenager, my family responded with curiosity, excitement, and confirmation. I was doing well, I was achieving status within my family. I was winning the game.

Earlier I mentioned my distaste for the status-obsessed drivers of expensive cars. I still have a negative reaction to showy displays of material wealth. That’s because virtue games were also important in my family, and virtue was defined in part by a disregard for wealth. Upper middle class comforts were expected, but flashy consumption was considered a sign of moral failing.

It took me years of meeting people from other families, other backgrounds, to recognize that assumptions of upper middle class comforts were a by-product of entitlement, and that for people who had to struggle to get past the circumstances of their upbringing, displays of material wealth carried entirely different meaning than what I’d been raised to believe.

Though we don’t like to admit it, we all play dominance games. The Army-Navy sports rivalry is well-known in the United States. And it doesn’t just manifest in games between the military academies of West Point and Annapolis. I remember one evening from my Army ROTC days, when we played a Navy ROTC team in intramural football. Think about the stakes here: Intramural football, no referees, watched by perhaps 20 or 30 spectators at most, with nothing more than bragging rights on the line.

We played our asses off. It was the most physical game of the season by far, and both teams put everything they had into the contest. My team won, and even though we finished the season well shy of a championship, winning that single game against Navy ROTC was an immense thrill. All of my fellow Army cadets celebrated the team’s victory. We gained status within our ROTC detachment. And whether consciously or not, we knew we’d gained status relative to the Navy ROTC team, and by extension their entire program. We had won a dominance game.

My girlfriend at the time couldn’t understand why we’d played so hard that one of my teammates almost broke a rib. “Why did you risk getting injured again,” she asked me, knowing that I was recovering from an ankle injury at the time, “when you know that could put your commission in jeopardy?” Then she drove the knife in deeper by pointing out the obvious fact that nobody would care about the game in a few weeks. None of her observations were wrong, but status games are powerful motivators.

I mention some of my own status games to illustrate three things: First, our perceptions of right and wrong, good and bad, are strongly influenced by the status games we play. Second, we often don’t have a choice in which status games we play, because we’re born into them. Third, status games that are wildly important to us can appear inconsequential at best and bizarre at worst to outsiders.

Bringing Status Games Into Your Roleplaying Games

No, I’m not talking about pitting your players against each other in status games. Status motivations can provide really useful character definition for both player characters and NPCs. Those motivations are particularly valuable because they’re so foundational. As Storr puts it:

Status is what researchers call an ‘ultimate’ rather than a ‘proximate’ drive: it’s a kind of mother-motivation, a deep evolutionary cause of many other downstream beliefs and behaviors that’s been favored by selection and is written into the design of our brains.

There’s no formula for determining the number and type of status games a given person may be playing, at least Storr doesn’t provide one. But it makes sense that individual circumstances dictate many of these parameters. How important is family, and how broad is it? Is work just something a person does because they have to, or does it provide them the bulk of their feelings of self-worth? What friends and broader social groups matter to a person?

Thinking of a roleplaying character, we can in a broad, unscientific way also examine predilections toward certain types of status games. While most status games are a mixture of dominance, virtue, and success types, as the above examples illustrate, usually one type takes the lead in a given game. And while a character usually is engaged in multiple status games, that person usually can’t rise to the top in all of them, leading them to put more energy into getting ahead in the games to which they are most suited.

I’m employed this approach to quickly come up with status motivators for NPCs. I haven’t used it with any player characters yet (why yes, I have been on a long run of GMing), but I’m excited to try at some point. In the mean time, here are three examples that demonstrate the technique I use for NPCs. Each NPC gets a dominance game, a virtue game, and a success game. Each status game is either first, second, or third priority for that NPC. Note also that these are all human characters. It could be interesting to experiment with different types (or lack thereof) and manifestations of status in other species.

Wakku the Info Merchant

Wakku is an NPC in my current Star Wars: Edge of the Empire campaign. He grew up on an out of the way Outer Rim planet and is the third of five children. His family was scattered during the war after a battle between Rebel and Imperial forces devastated the region surrounding his home settlement.

- Dominance: Wakku is physically small and unintimidating. He is neither physically nor mentally dominant, and has barely escaped several firefights. He abhors violence, in fact. Playing for any kind of dominance is the last thing on his mind, and every time he has to play dominance games, he loses. So he avoids them whenever possible.

- Virtue: A disciple of the philosopher Trairr Graul, Wakku wants to impress other followers of Graul with his understanding of and adherence to Graul’s teachings, which elevate nonviolence and psychological manipulation of enemies. He would never admit it even to himself, but to be recognized by the Graulian Council as a Third Tier follower, even though it conveys no material benefits, would fill him with pride.

- Accomplishment: While he believes in the teachings of Graul and wants to be recognized for his virtuousness in that respect, more than anything Wakku desires recognition for his ability to outsmart others. He’s self-aware enough to understand and cultivate this overriding status motivation, and it gives him immense pleasure whenever he uses his wits to obtain information, money, or power. It gives him even more satisfaction when people praise him for it.

Imperial Remnant Admiral Lers Grimmat

Lers grew up on Corellia, and always knew he was destined to command star ships. Three generations of Grimmats before him served in the navy, his father dying in an early battle against the Rebellion while commanding the corvette Decimator.

- Dominance: Lers wants to dominate the New Republic in battle and to be part of a remade Empire. But his personal presence is not overpowering. He does not cow subordinates. In fact, he has discovered that he can exercise control better from behind a desk than by appearing in person. In political battles with other officers, he wins through planning and careful manipulation of the bureaucracy. Lers gets what he wants, but not through dominance.

- Virtue: You don’t wind up an Imperial Remnant unless you believe in the cause. And Lers does. He values order and authority. He runs his fleet with an iron fist, seeing the exercise of authority as adherence to the Empire’s mandates. Lers is known by his subordinates and peers as a man of the Empire, through and through – a manifestation of it’s highest virtues – and he enjoys that reputation.

- Accomplishment: Succeeding in high-risk situations is of utmost importance to Lers. When he makes military plans, in the back of his mind there is always the idea that he will be judged by his peers not just for winning battles, but for doing so in dramatic fashion. The Admiral will take huge risks if he thinks they’ll give him a shot at this kind of glory. What he doesn’t realize is that his fellow Admirals and other Remnant leaders only care about the long-term success of their plans. He’d have better odds of winning the accomplishment game if he focused more on simply defeating the enemy, but stories of his father and great-grandfather’s wild victories has warped his perception.

New Republic Alpha Blue Agent Jae Ronkins

Jae was always in trouble as a kid, usually for questioning authority. She was also a star speedball player. Her brawn, agility, and ability to think on her feet took her all the way to the Imperial Ground Officer Academy. After graduating she took command of a platoon and was thrown into battle, where she demonstrated a knack for beating the odds. She quickly moved from Platoon Leader to Section Commander, before her questioning nature caused her to defect to the Rebellion. Jae then won battle after battle for the Rebellion, but decided after the war to hunt down Remnants as a New Republic Agent.

- Dominance: Jae enjoys being an agent, because she treats every hunt as a personal matter. As in speedball, there can be only one victor. Jae doesn’t mind losing at sabbac or other non-physical activities, but get her in a speedball court or give her an assignment to nab a Remnant, and she will move heaven and earth to make sure she’s the victor. Jae is a winner, and though she thinks of that mentality as purely personal, it’s also how she wants others to think of her.

- Virtue: Service in the Imperial Army was never more than a means to an end for Jae, and she didn’t think much about why she was fighting. But repeatedly she saw Rebel troops make immense sacrifices in battle in order to protect their comrades and defend civilians, while she was lauded by her Imperial superiors for leveling towns and killing innocents. She couldn’t win this virtue game. She didn’t want to play it. So she switched sides and played the Rebel’s version, which suited her much better.

- Accomplishment: Because she doesn’t like to lose, Jae wants to be perceived by her peers and superiors as capable and effective. But she has never cared much for accolades. Jae has medals for bravery, for battlefield victories, for saving lives. She’s a living legend in the (agency), and is winning the accomplishment game. Her peers hold her in the highest regard. She just doesn’t think much about it, even though her success in this game provides her many advantages.

Games Without Frontiers

There are many ways to think about and generate NPC and PC personalities. Think of status as just one more lens, another way to come up with ideas. If you’re curious about status and how it affects us all, I highly recommend The Status Game: On Human Life and How to Play It. Will Storr is an engaging and sharp-witted writer who backs up his assertions with deep research.

Image Credits

The photo of Jim Jones is a cropped and color adjusted version of File:Jim Jones, 1977.jpg - Wikimedia Commons by Nancy Wong, which is available under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license, as is this edited version.

Ω