Why is it that there is no moral panic about computer RPGs in the way that there was in the early days of tabletop roleplaying?

You can either read the post below or watch it in video form (added 2024-03-30).

Tabletop roleplaying games were initially known as fantasy roleplaying games. Over time the term of choice became roleplaying games – RPGs. Then somewhere in the 1990s the term shifted again, to tabletop roleplaying games and the unwieldy and unsatisfying TTRPG acronym.

Why? Because RPGs became the province of digital roleplaying games. It’s no secret that the computer games industry is mammoth. It’s a $64B market, which is greater than the annual defense spending of Germany and bigger than Nike’s annual global revenue.

Meanwhile, even in a Golden Age of tabletop roleplaying, the TTRPG market is orders of magnitude smaller. The original face-to-face analog mode of roleplaying has been thoroughly supplanted by its digital offspring. And though we still call it tabletop roleplaying, the dominant format in the hobby is now online play facilitated and streamed to observers by digital tools.

It’s obvious that improvements in technology, particularly those that allow people to connect, play, and watch regardless of geographic separation, are responsible for this transition away from face-to-face play. But there’s more to this story, I think.

Keep It Secret, Keep It Safe

Even in the early days of computer RPGs, they weren’t subject to the kind of fear and dismissal that often greeted tabletop RPGs in their early years. Yes, fantasy roleplaying games were wildly popular by the time my junior high friends and I latched onto them at the dawn of the 1980s. But they were also famously fodder for the Satanic Panic and attacked for being instruments of the Devil. And even in places where D&D wasn’t associated with demonic rites, advertising one’s self as a “D&D nerd” was scrupulously avoided. I had jock friends, surfer friends, and popular-for-various-reasons friends, and we all kept our gaming habit somewhat cloaked.

That was the story for many roleplayers of that era. But I noticed something as computer roleplaying games exploded onto the scene: Nobody looked at them with suspicion. Yes, there were parents who were concerned about early computer RPGs. But the objections were similar to those leveled at the movie Fast Times at Ridgemont High or the song Cop Killer – the games were ostensibly speaking to teenagers about things (underage sex in the former, violence in the latter) that offended parents. The objections were about substance, not form.

Some of this more muted reaction can probably be attributed to everyone being exhausted by the Satanic Panic. Still, at least in the United States, I suspect a more fundamental force was at work.

Technologic

Computer RPGs are technology. They are progress. We Americans are comfortable with that. Tabletop RPGs, however, are books. Specifically they are books that invoke imagination, books that define fictional worlds, worlds that don’t operate the way our world does. They are arcane. Many Americans are definitely not comfortable with that.

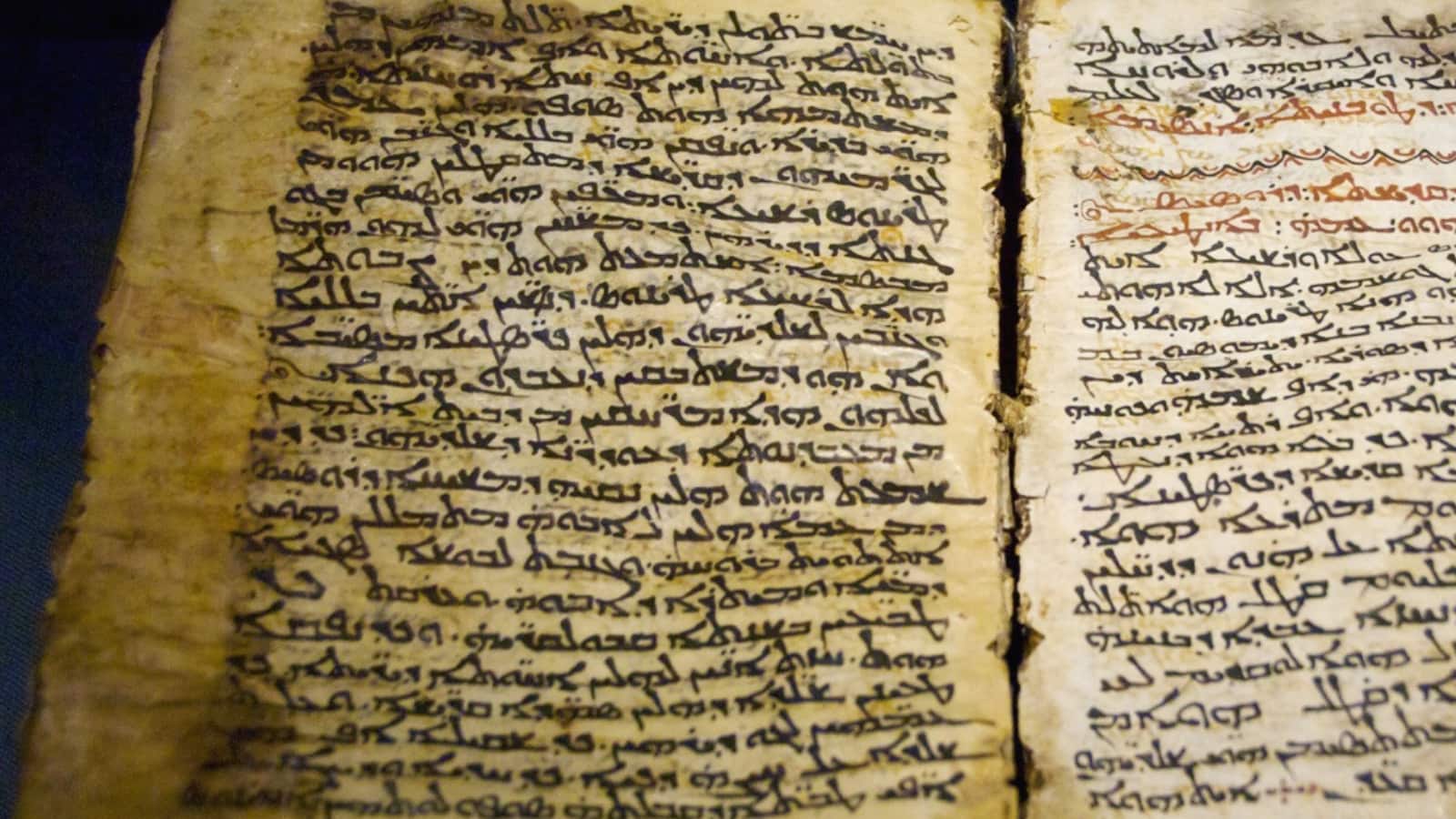

That which is arcane is secret, known only to a few and mysterious to those who don’t know it. You have to devote time and attention to a book in order to know what it’s about, to absorb and understand it. Explaining a book often isn’t easy, and the only way to truly understand a book is to read it yourself.

Contrast that with a video game. What is a video game? Well, look, see how I’m moving my fingers on the keyboard and my Paladin is fighting orcs on the screen – that’s a video game. The nuances of how to most effectively play the game take time to master, but there is nothing secret, nothing hidden beneath the surface or requiring interpretation.

Video games are also played on devices that represent the cutting edge of consumer technology. These devices are produced by publicly-traded companies and purchased by millions of people across the globe. They bear the imprimatur of progress, convenience, immediacy, the future.

There’s something that happens when a fantastical story birthed as a book becomes a video game, TV show, or movie — it becomes accessible, which is to say easily absorbed. Tolkien’s Middle Earth books sold like hotcakes for decades, George R.R. Martin’s tales of the Iron Throne were wildly popular, and the Expanse series were all bestsellers. But even after Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings movies crushed box office records and Game of Thrones became the hottest thing in streaming, admitting that you enjoy the books behind those blockbusters identifies you as perhaps a bit too interested in the fantastical. There’s something about that degree of immersion that many people find unsettling.

Mazes & Monsters

Tabletop roleplaying books are even more unsettling. They are not just journeys into imagined realities, they invite participation in those worlds. In a very real sense, they are gateways. And, horror of horrors, the power of these books is such that they can bring people into imagined worlds without the benevolent, homogenizing hand of digital technology.

Is it any wonder that some number of credulous and fearful parents saw Dungeons & Dragons as a malevolent force? If it wasn’t enabled by technology, and it offered a pathway into inhabiting imagined realities, how could that not be an encroachment into magic and belief? How could that not be an affront to spirituality, one of the few areas that can’t be safely given over to technology’s governance? And if you already believe in the Devil, it’s not much of a leap to accept that those D&D tomes could be the Devil’s way of providing foul instructions to young minds. Spells, after all, reside in books.

Today

Thankfully, though fear and loathing are still manifestly endemic to the human condition, the fiery eye of misplaced moral panic is no longer pointed at tabletop RPGs. I’ll submit though, that much of this is because the public face of our hobby is now digital, radiating the warm, comforting glow of technological progress. Let us not speak of the books that still lurk in the shadows, arcane and unknowable to those who dare not uncover their secrets.

Ω